Entering a copper mine deep inside a mountain was one of the more awesome things we did on our trip to Arizona. Gathering inside the main building at the Bisbee Copper Queen Mine, we explored the rocks for sale inside the gift shop until our group was called.

We were each given a brass tag with a number, like a real miner. These would survive in case of an explosion or cave-in to identify the bodies. This was called “brassing in” when miners reported for duty. At the end of his shift, the miner would turn his tag back in to the timekeeper. Here’s a replica from the Bisbee historical museum of the timekeeper’s station.

Then we each went along an assembly line to get outfitted. With assistance from a seasoned miner, we donned yellow slickers, lights around our necks, belts and helmets. From here, we boarded a tram for our ride into the mountain. We sat astride like on a horse. A bell clanged, and the tram jerked forward. A gap yawned in front of us as we moved ahead. Wheels creaked as we entered a dark tunnel with chiseled rock walls.

We glimpsed other passages leading off into pitch blackness as we rattled deeper into the interior. Rocks glistened in places from crystals. Dust-covered ore carts and discarded tools lay about. The only way we could see in the dark was with our lights. Wood supports shored up the walls at intervals. Loose rock was “barred” or secured behind metal bars.

This mine, unlike others, was cool with a temperature in the fifties. That’s because air flows in from outside. We rode horizontally into the mountain. Other mines go straight down. Those mines are hotter and need air pumped in. This one evolved from a natural hole and was discovered by army scouts in 1877. Because methane gas wasn’t a danger here, miners could smoke in these tunnels. However, the men had to hand roll their cigarettes so they would go out if dropped.

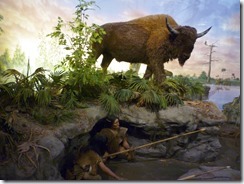

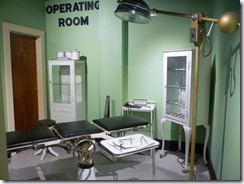

Riding on the tram, I felt someone tap my head. I twisted around. My husband hadn’t done it. Who, then? A ghost? Mines were rife with accidents: explosions, cave-ins, tumbles down the shaft, falling rock. Who knew how many workers had died there? Unexpectedly, lots of orbs showed on some of my photos. Spiritual entities or dust motes? More scenes from the museum.

Eventually we came to a stop and got off at a big dug-out chamber where our guide explained about mining methods. Miners worked by candlelight and swung a pickax to break off rock from the walls. If the rock was too hard, they drilled holes in the rock using a steel drill bit and a sledgehammer. They’d put in a stick of dynamite and light the fuse. This broke up the rock and expanded the tunnel. They’d transport the ore to chutes. It went down into ore carts which were pulled by mules. The mules lived in the mines. When their time was up, they were taken to the surface with blinders on and their vision gradually restored so they didn’t go blind from the brightness.

We saw the metal toilets where early miners did their business as they toiled for 12 hour shifts underground. Those seats must have been chilly!

If a miner needed to reach the surface, he’d tug a rope pull by a cage. The cage operator would send down the open wood platform. We saw the boss’s tricycle (or similar conveyance) by which he checked on his men twice a day.

They pumped in air and water. The water cut down on dust, which could damage the lungs. The compressed air was used in machinery-operated drills once they became available. Today, the mines are tested for radon gas. Other types of mines have to be tested for air and methane gas. You can light a candle to see if there’s air flow. Parakeets were used to detect dangerous gases. Miners would equip themselves with a helmet, candles and matches, lunch pail, and sometimes a survival kit or gas mask.

Copper doesn’t deposit in veins like gold. It’s mixed in the ore, so processing techniques are needed to separate it from other substances. It would have been sent to a stamp mill for crushing and refining. Side products could be gold, silver, zinc, lead, and other minerals.

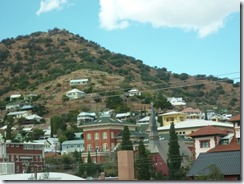

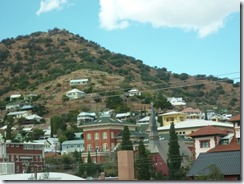

I learned a lot more when we went to the history museum in Bisbee, after a pleasant lunch in town. Bisbee is built among the hills and has some interesting shops and restaurants as well as a historic hotel.

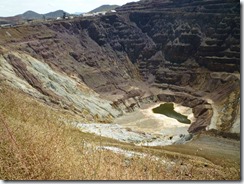

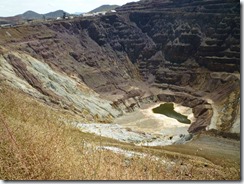

I won’t bore you with further details about mining, but they were fascinating. The method used today is called the open pit technique. You can see the results at the Lavender Pit. It’s not a pretty sight.

Disclaimer: Any inaccuracies are due to my note taking and not the information presented.

You can see more photos here: http://fw.to/SB2DmEH

<><><>

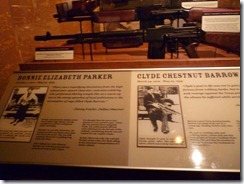

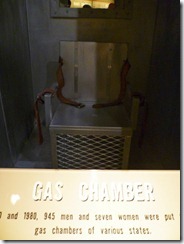

How does this relate to my story? In Peril by Ponytail, Marla and Dalton are staying at an Arizona dude ranch owned by his uncle. Raymond is also renovating a ghost town that used to be a former copper mining camp. Marla’s exploration of a hillside where a worker vanished leads to an astounding discovery. Consider the information above and use your imagination to determine where Marla and Dalton find themselves next.